It is beyond annoying that when a conflict erupts, everyone seems to become an expert, whether it’s the Russia-Ukraine war that began in February 2022 or the Israel-Palestine attacks of October 2023. The truth is even seasoned experts and post-doc researchers struggle to provide definitive answers. Rather than peddling a half-baked theory of peace in whatever region has the hottest conflict, I’m taking a step back to examine the broader, albeit equally grim, picture. I believe this perspective may offer a more suitable explanation. So, let’s dive in.

The history of humankind is knitted inextricably with the tale of territories changing hands. While there’s a line in the Bible that says, “the meek shall inherit the earth,” this inheritance remains unclaimed by a docile people. Instead, powerful groups have often disguised invasions with noble motives like “for God and country.” Even in the 21st century, where war is frequently seen as a relic of the past, the narrative of conquest persists. Is this tendency to overpower, vanquish, and subjugate something humanity evolves from, or is it innately part of who we are as a species?

The Question: Is Irredentism the Natural State of Geopolitics?

Irredentism is the principle or policy advocating for the annexation of territories based on shared ethnicity or historical possession. In simpler terms, it’s the concept of taking over someone else’s land for a semi-substantive reason.

Historical Examples of Irredentism

Italia Irredenta

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Italia Irredenta movement advocated annexing territories with ethnic Italians under foreign rule, notably the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Areas like Trentino-Alto Adige, Istria, and Dalmatia were annexed into Italy after World War I through the Treaty of Saint-Germain (1919) and the Treaty of Rome (1920).

Greater Croatia and Greater Serbia

Both movements aimed to unite all ethnic Croatians and Serbs into single nations, targeting regions within the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires, including Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Vojvodina, and Dalmatia. These ambitions intensified in the 1990s during the violent breakup of Yugoslavia.

Greater Hungary

The Greater Hungary concept sought to restore Hungary’s pre-World War I borders, which were significantly reduced by the Treaty of Trianon (1920). The Treaty stripped Hungary of about two-thirds of its territory, including parts of present-day Slovakia, Romania, Serbia, Ukraine, and Austria.

Megali Idea

Originating in the early 19th century, the Megali Idea aimed to unify all Greek-speaking and Greek-populated regions into a single Greek state. This concept emerged during the Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire.

Manifest Destiny

Manifest Destiny was the 19th-century American belief that the United States was destined to expand from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. This expansionist ideology disregarded the rights of Native American peoples and other claims, ultimately achieving its goal of continental expansion.

China and Taiwan

The China-Taiwan issue involves the PRC (People’s Republic of China) claiming Taiwan as part of its territory under the “One China” policy while Taiwan operates as a separate entity. This division originated from the Chinese Civil War, when the Communist Party established the PRC and the Nationalist Party retreated to Taiwan.

The Idea of Kurdistan

The Kurdish aspiration for an independent Kurdistan involves uniting Kurdish populations across Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria. Despite ongoing nationalist efforts, Kurds remain stateless and face significant geopolitical challenges. Their aspirations for statehood have been intermittently supported, particularly when aligned with broader regional politics.

The Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands are a British Overseas Territory claimed by Argentina, which refers to them as the Malvinas. The issue escalated in 1982 when Argentina invaded the islands, leading to a brief conflict with the United Kingdom, resulting in reaffirmed British control. The sovereignty dispute remains unresolved.

French Canada

French Canada, primarily Quebec, represents French-speaking Canadians’ historical and cultural desire to preserve their distinct identity and, at times, seek greater autonomy or independence. This sentiment led to the separatist Quebecois movement’s rise and the Parti Québécois’s formation.

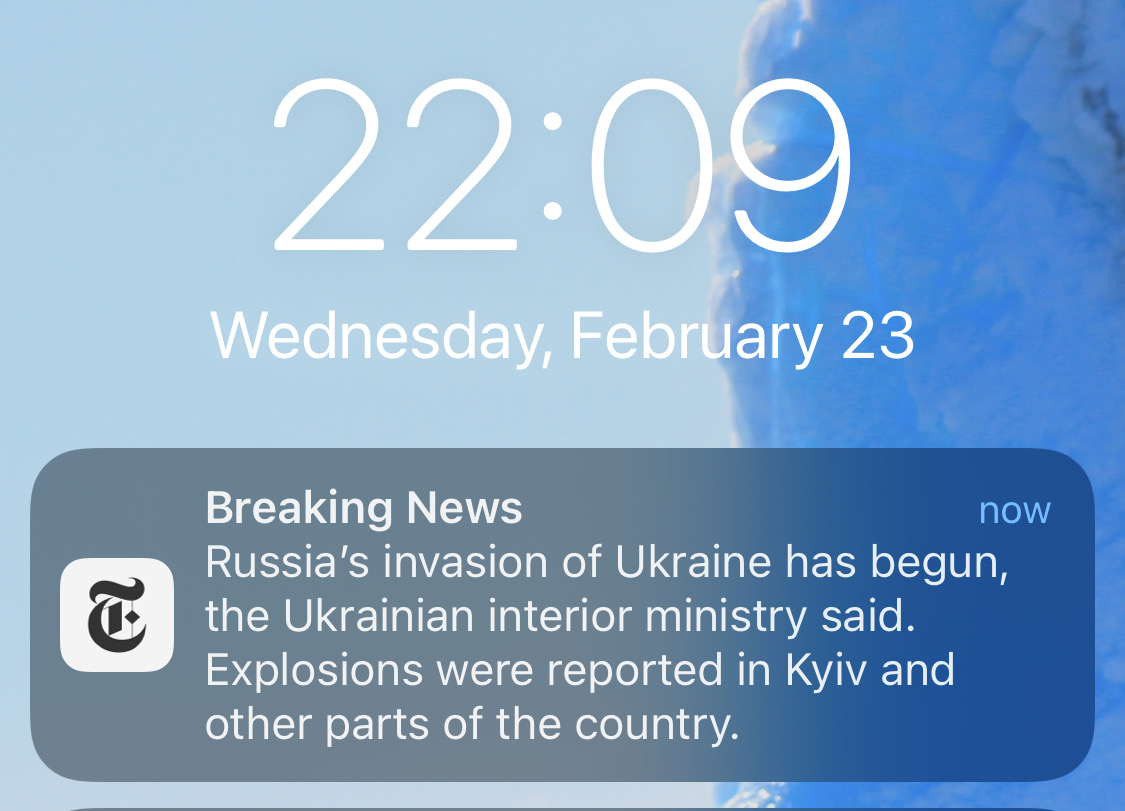

Russia and Ukraine

The Russia-Ukraine conflict involves territorial disputes and national identity issues, particularly concerning Crimea and Eastern Ukraine. Following the Soviet Union’s collapse, Ukraine became independent, but Russia has challenged this status, especially after annexing Crimea in 2014 and supporting separatist movements in Eastern Ukraine.

Israel and Palestine

The Israel-Palestine conflict centers on competing national aspirations and territorial claims over the land between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River. Key issues include the establishment of a Palestinian state, the status of Jerusalem, and the rights of refugees. Despite various peace efforts, a lasting resolution remains elusive.

Etcetera

Even in this short list, it becomes apparent that many conflicts are rooted in some form of irredentism. Others that might ring a bell include Gran Colombia, Paraguay and the Triple Alliance War, Ecuador and Peru (The Cenapa War), Australia and Aboriginal Land Rights, Greater Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan, Somaliland, Nigeria and the Bakassi Peninsula… the list could go on.

Oh, and even Antarctica

We find stories and scars of irredentism on every continent—even Antarctica. Global powers took decisive action to prevent irredentism from encroaching on the seventh continent. The Antarctic Treaty, signed in December 1959, establishes Antarctica as a zone of international cooperation focused on scientific research and environmental protection. It ensures that Antarctica is used solely for peaceful purposes and suspends any claims of sovereignty. Without these measures, irredentism could quickly emerge, with disputes over areas explored by figures like Ernest Shackleton—who, though Irish, sailed under the British flag. Such a scenario would soon devolve into a tangled mess.

Territorial Integrity: A Futile Dream?

Could we throw off irredentism and stick to territorial integrity? Could we, as a species, stop trying to recreate and create new borders and accept the status quo? Many would say yes but then argue over which status quo. After WWII? Before the dissolution of the Soviet Union? Before Columbus came to the Americas? It’s impossible to pinpoint a moment and say, “Here, we freeze territorial integrity.” That would only lead to a massive backlash of irredentism.

Our Nature: Irredentism as Inherent?

Change is inevitable, and so, I believe, is irredentism. It is ingrained in the human condition—a reflection of our desire to reclaim what we consider ours, to seek community through shared language, ethnicity, and history, and to connect to something larger than ourselves. I neither favor nor oppose irredentism nor do I condone the violence it often entails. Instead, I recognize it as a reality of life. Irredentism and territorial integrity are two sides of the same coin—sometimes we land on heads, sometimes on tails, and sometimes we toss again.